Sugarcane 11-11-20

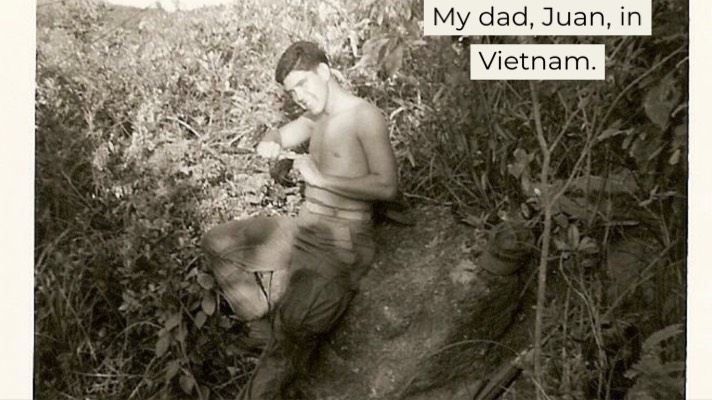

It’s Veteran’s Day 2020, and I think about my dad, who is a veteran and very much alive and well. When he was in Vietnam, he literally lived in the bush for ten months. He was in “Utter’s Battalion,” and anyone who knows the story of Lt. Col. (at the time my dad served for him) Leon Utter, knows this man led his men into one operation after another. My dad was wounded many times, but he kept going back and continued to fight.

Because he was in the jungle, and it was 1965-66, the very early years of the Vietnam Conflict, and because Lt. Col. Utter never pulled his men out of that habitat, food could be scarce. My father recalls eating grubs, roaches, and other bugs we would turn our noses at. However, the one thing he found in abundance in Vietnam was sugarcane. Thank goodness for the sugarcane. It acted as a relief to the constant protein nightmares he had to eat in order to survive. Because he grew up very poor (but very loved by his grandmother) in Laredo, Texas, and sugarcane grew wild, he knew how to spot it. Like mesquite pods (what he refers to as “candy”) sugarcane was part of the natural sugars he indulged in as a child (when he could find it), especially since store-bought candy was not affordable.

My parents teach me the old ways. They tell me it’s because “nunca sabes,” you never know when it will come in handy. My dad’s time in Vietnam proved that he could survive in more ways than one. Thank you for the lessons and thank you for your service, Dad. Semper Fi.

El Día de los Muertos

I miss my grandmothers. This time of year is about remembrance. El Día de los Muertos is around the corner. Except for food and drink, my alter is done. My dad’s grandmother, Eufemia, would often tell stories about her life on the Rio Grande while lighting candles, preparing for “El Día de los Muertos.” Food and drink were placed on the alter for the dead: pan de muerto, conchas, tequila, water, café, soda…whatever they loved to eat and drink when they walked the earth with us. Yerbas would be consumed or burned. Comino, Oregano, Garlic and Cilantro are some favorites of my maternal grandmother who used them in beans and rice, as well as deer meat for her tamales to get rid of the “game” taste. However, the big one is Copalli incense made from the resin of the Mexican Copal tree. Burned at the altar, this resin said help guide the soul to heaven. These are burned, by the way, not only at the alter inside your home, but at the cemetery. Candles, liquor, food and Copalli are brought to the cemetery where an all-night vigil takes place. There is música, storytelling, prayers, tears, laughter and, above all, tremendous love for your family.

In places like the border (where my entire family, on both sides, and I are from) the celebrations and remembrances are taken seriously. My mother remembers sugarcane, which was length and width of a broom handle, (vendors would be outside the cemetery with stacks of them) was chewed for it sweet juices and spit out (because you aren’t supposed to eat the weave). Dulces Mexicanos were a particular favorite to eat as well, such as “calabazate,” a pumpkin candy that is hard on the outside and gooey inside with pumpkin and sugar, leche quemada, and grated piloncillo mixed with shredded queso blanco on top of a corn tortilla, rolled like a cannoli, and then heated (my mom’s mother, Soledad, would make this and it is so good)!

Let us not forget it is also Halloween (celebrated by Border-Latin cultures on both sides of the Texas-Mexican border in Laredo and Nuevo Laredo), which is day one of Día de los Muertos, because at midnight on October 31st, the gates of heaven open and the children can rejoin their families, first, on “El Día de los Inocentes” for twenty-four hours (November 1st), followed by “All Souls Day” or “Day of the Dead” (El Día de los Muertos) on November 2nd.

In honor of the three-day holiday coming up in less than a week, I offer you a story tol to me as a little girl by my father and great-grandmother. I rewrote this story and delivered it in 1992 for an intercollegiate oratorical contest called, “Battle of the Flowers Oratorical Contest” and won. I have since updated and edited the manuscript from the original version.

Now I bring you the most famous of deaths…the story of “La Llorona” or “The Weeping Woman,” written by me and told through the point of view of my great-grandmother.

La Llorona

By María Cristina Gutiérrez-Boswell

My name is Leonor Paredes and I was born at the turn-of-the-century in September 1898. I was born in the locality of Nuevo Santander, along the lower Rio Grande border. We know it today as the place of the two Laredo’s. But I was born north of the river. I have a story to tell you about a woman who had the conscience of El Diablo, that tricky and evil spirit who roams the earth and lures men into the very bowels of tierra madre.

This is the story of a woman who haunts the banks of the Rio Grande and who searches for her three children. She is known as La Llorona. But for those of you who have forgotten the mother tongue, you may call her “The Weeping Woman.” Let me tell you her story.

La Llorona lived in a barrio called The Devil’s Corner in Laredo, Texas. La Llorona and her family lived in a broken-down shack. They were very poor. Work was hard to find. They were lucky if they had one meal a day — usually frijoles and tortillas. Because she was beautiful, her father thought that he could marry La Llorona off to some wealthy hacendado, a man who owns a hacienda and employees many vaqueros, indios, and peones to run his rancho.

Such was the father’s hope. But the mother knew better for they were poor and could offer no dowry. Still the father tried, hoping to better himself from a good trade. La Llorona, however, had dreams of love.

“Love! What good is love! “Her father would say. “When your family is starving? You will marry the man that I choose! I gave you life and now you owe me yours!”

La Llorona thought about what her father had said. She loved him dearly and would do anything to please him. Yes, she thought, children do not live for themselves, they only live for their parents. Still, she prayed that one day she might find a man whom she could love and who would also be acceptable to her father.

One day, such a man did arrive. He was a young hidalgo, a somebody—the son of a wealthy gentleman. He took one look at La Llorona, gazed into her shining eyes, and fell in love with her. She was happy. Her father, for the first time in many years, went to church and thanked El Señor, our Lord for his buena suerte. He went to the cantina and while drinking tequila bragged to his friends that soon he would be living ina beautiful casa with many rooms, own a large, carved dining table, and have a view of the river.

But all was not well.

The young hidalgo’s parents were opposed to the match. They too had hoped for good things for their children. And they hoped that their handsome hijo would find a young woman of a good family and breeding.

Against the wishes of his parents, the young Hidalgo eloped with his dark-skinned, black-haired, La Llorona. The church had not blessed the marriage. Nor had the parents of the groom granted their blessing either. They disinherited Nothing but sadness, they said, would come of their son’s disobedience. The young couple held out, trying to be together through the mala suerte. But one cannot live on love. To support her family, La Llorona worked as a seamstress. To make ends meet, she worked nights at the cantina. Her husband had become a borracho, or a drunk, squandering what money they had, pretending to be somebody.

The hidalgo’s parents never changed their minds about Llorona. They would accept him but not Llorona and their grandchildren. They still believed he should marry someone more suitable. He refused at first and thought of his children. But his parents reminded him that La Llorona had worked at the cantina. The townspeople made “jokes” about him. “Your children have dark eyes and skins,” his parents said. “None of them look like you. Why don’t you leave your mistakes and start over?”

*******************************************************************

“I’m going away for a while,” he told La Llorona. “This town has nothing for me. I need to find work.” Weeks passed. La Llorona did not hear from her husband. Then months. Finally, word about her husband reached her. He had married again. Now he raised horses and won many races. His new wife was about to give birth to their first child

La Llorona could not believe her ears! Her days of work grew pointless. She could not sleep in her bed. She looked into the eyes of her children and saw only the eyes of her husband. In time their eyes mocked her, and she learned to look at them as if they had no faces. At times, she would look out of her casita’s window and watch them at play. Their laughter sounded like the shrill cries that horses make when high winds blow across the plains and lightning flashes against a black sky. She could not bear their eyes or their laughter. She took them to where the river turns and whirlpools play. Atop a high rock, she urged her children to jump. She would join them soon.

********************************************************************

You can see her there when the moon is full, calling them by name. “Ramoncito! Pedrito! Where are you my little Juan!” Then she breaks into tears and her youth and beauty wrinkles and she asks: Dígame! Dígame! Dígame! Tell me! And finding no answer, she laughs and flies into a rage, “How dare you judge me!” She cries, to the unlucky passerby, “What do you know about a mother’s love? What do you know about a woman’s despair?”

It is said that when La Llorona’s soul went to heaven, Saint Peter refused her passage through the gates. “Where are your children?” And she replied, “I do not know.” Therefore, Saint Peter sent her soul back down and told her to search for her children. Now, she lives on the banks of the Rio Grande, damned and cursed. Men, especially, need to beware. If you happen to see a beautiful vision of a woman wearing a white dress, do not approach. Do not ask why she is at the edges of the murky water. Do not let her turn around and look at you. To see her is to see a face of a horse, or worse, no face at all. To do so means a lifetime of fear and psychotic breaks, or a sudden death.

______________________________________________________________________________

My Father’s Side of Yerba Bella

Mis abuelas, who I often invoke in prayers to the universe, evoke great comfort. My great, great, great grandmother, Maria Renteria was a full-blooded Lipan Apache woman. Her daughter, Petra, was a soldadera in Pancho Villas army, and her daughter, Eufemia, raised my father. It was Eufemia who brought the curanderismo to life, using spells, incantations, and “Las Doce Verdades del Mundo.” This was the ultimate demonio/bruja- destroying prayer. Eufemia lived in “La Azteca,” a neighborhood edging the Rio Grande in Laredo, Texas. Curanderismo cured everything, from “El Ojo,” or “Mal de Ojo” (the Evil Eye), to the flu. Pirul, or a Mexican peppercorn tree, dusted the body for spiritual cleansing. El huevo, or “the egg” was rubbed and rolled in a “sign of the cross” pattern all over a person to determine if Ojo or Mal de Ojo was used by someone, intentionally or unintentionally, to bring sickness to the person whom upon they stared. Also, the herb Sage has been used, dried and lit, allowing the smoke to envelop the person seeking relief.

The rope was used in Las Doce Verdades del Mundo (The Twelve Truths of the World) to rid the neighborhood of bad luck. la lechuza, or the owl, was usually a sign of a demon or a witch in the neighborhood. It is also a sign of death to the Spanglish culture of Mexico and Texas. Hearing the owl, meant death was coming to someone close to you, if not you. It also meant, bad luck. Therefore, Las Doce Verdades was recited to bring the demon/witch out of hiding to be killed. The prayers, Catholic and pure, had to be said by a group of ladies with precision and speed, with a knot tied onto the rope following each prayer. According to my father, who witnessed this prayer being led by his grandmother, Eufemia, they would finish, grab the rope, throw it to the ground and stomp their feet. It was then the witch would appear. Often times the only sound heard was a cacophony of chanclas splattering the ground, followed by blaming each other for not saying it correctly or fast enough when the demon or the luck would not go away. However, one time, according to my father, an owl fell out of the tree after. “It was already dead, it seemed…probably died from being scared to death by the women yelling and slapping the ground. But, all I heard, was twelve ladies yell ‘BRUJA!’ And all run to it with their brooms and beat the hell out of it. Afterwards they carried through the neighborhood screaming, ‘¡Ya matamos la bruja!’ (We killed the witch!). Still, the bad luck never really went away, but in that moment, there was a big, beautiful hope that the neighborhood experienced. We all came together and celebrated the victory!”

Francina Alekna says:

I could not refrain from commenting. Perfectly written!